Think you’re good? That means you’re stuck in mediocrity. When we feel competent, we become arrogant and fall in mediocrity.

The following is a story about running. But it applies to anything where you want to become better, from weightlifting, to piano playing, to coding, to painting.

I was stepping on the podium to receive my award for the race. It was the first time I had ever won in a running race. I had never come close before. And it was after I had cycled 30 km to the start line. And only three weeks after my first ultramarathon over 100 km.

I felt I had this running thing in the bad. I would only get better and better. Win more races, do longer distances, get better and better. I just had to keep doing what I was doing.

Eight years later, I was worse. I had not won any other races. After some injuries and lack of training I was slower than before.

What happened?

My running journey is (yet another) time I learned the lesson of the Arrogance Curve. And it’s why now I am finally improving again, after almost a decade of stagnation-decline in running performance.

Act 1: Beginner Becomes Good

Running sucks

I always hated running because I wasn’t good at it. As a kid, I played water polo and tennis and later competed in mountain biking. But running felt like it was for lighter, more graceful people—not me.

Running does not suck

Then, I joined a work relay race. To avoid embarrassment, I trained hard. At first, it was painful, but eventually, I improved. On race day, I finished a 5K faster than I expected, though still slow by most standards.

I got hooked. I started running regularly and entered trail races, progressing from short distances to a half marathon, which was tough but rewarding.

The first fall

I signed up for my first mountain marathon, overconfident and undertrained. After an unplanned road marathon, I attempted the trail marathon but had to quit when my knees gave out.

Determined, I researched running techniques, read Born to Run, and bought Five Fingers to train my forefoot strike. After eight months of calf pain, my knees were fine, and I never had issues again.

With better technique (and bigger calves), I returned to trail races. I completed my first trail marathon, then another, and within a year, I ran a 110 km ultramarathon. Three weeks later, on a whim, I entered a forest half marathon and landed my first podium.

I felt unbeatable.

In truth I was already beaten. I just did not know it yet.

Act 2: Good Becomes Mediocre

In the following years, I didn’t improve. I trained the same, ran the same races, and got the same results. But my upper body weakened, and my cold resistance vanished. I felt like a T-Rex—big legs, tiny arms.

I took up CrossFit and enjoyed the beginner’s progress. For the next five years, it was mostly CrossFit and little running.

After moving to the mountains, I resumed running and ski-touring, getting back to my previous best but not beyond it.

I was stuck in mediocrity.

Why?

Act 3: Arrogance Curve

Because I had become arrogant. I thought I knew how to run and how to train to run.

This made me do the same things over and over again. Like a madman, I expected different results. But it was unavoidable due to the arrogance curve.

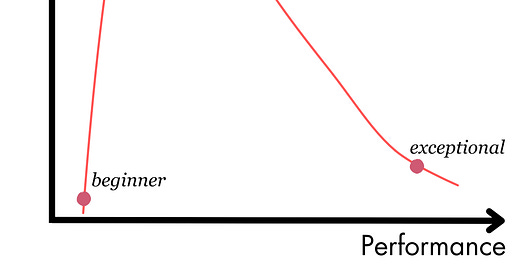

This chart plots arrogance on the vertical and performance on the horizontal.

A beginner starts with low performance and low arrogance. I had no clue when I started running, so I was open to learning, experimenting with techniques, and adjusting based on feedback.

As you improve, your performance and confidence grow until you hit the peak of the arrogance curve—where I was in my running journey.

At this point, you believe you’ve mastered the activity, but your progress stalls. This is the mediocrity trap, where many get stuck, repeating the same things that once worked because it’s familiar and part of your identity as a "good runner."

People at the peak of arrogance stop learning, rejecting new insights that challenge what they think they know.

This is the mediocrity trap. Most of us fall in this trap and never get out.

You repeat the same things because that is what got you there from the lower level from before. So it is proven.

But also because at this point, you have built your performance in this activity as part of your identity. After so many years, and so many races and kilometers, I considered myself a good experienced runner. This meant I had to know how to train and run well. Otherwise I would feel threatened that I was not actually such a good runner.

A pianist plays the piano in the same way. An experimental researcher devises similar experiments. A philosopher repeats the same ideas. A YouTuber create videos with the same format. A writer writes about the same things in a similar style. A musician creates variations of the same music.

People at the peak of the arrogance curve don’t learn. They unconsciously reject all new information. Any insights that contradict what they already know and do are threatening.

Exceptional performers stay humble and open to learning. They're never arrogant about their knowledge.

I'm far from exceptional, but I’ve escaped the mediocrity trap—for now. How?

Act 4: The Mediocre Becomes Humble, and so Progresses

I can’t take credit. I didn’t realize I was arrogant or plan to escape the mediocrity trap—I was stuck in it for years.

It was external events that humbled me. I felt slow compared to others, got recurring injuries, and saw no improvement despite all my effort. This made me question my approach. Feeling insecure was uncomfortable, but it opened me up. Instead of dismissing new information, I embraced it.

For months, I’ve been learning about running technique, training, and even shoes. I’m not winning races, but I’m faster, less fatigued, and actually enjoying running again.

Now, running feels playful and experimental. I try new techniques and training without worrying about expectations. I allow myself to make mistakes, analyze them, and adapt.

It's fun again, and that means I’m improving.

Act 5: The Humble Insights

Always humble

We all fall into the mediocrity trap—it’s human nature. The sooner you recognize it and escape, the faster you progress. If the best in the world stay humble and keep learning, so should we.

The signs are easy to spot if you know what to look for. You speak with authority, feel the need to advise others, and believe you have the answers. But your performance stalls, and you get defensive when challenged by new information.

Open but skeptical

The risk of always being open to new information is that you might take in wrong information. Being humble does not mean you believe everyone’s opinion. It means you are willing to analyze it.

You should be skeptical of any information. There are two ways to judge information validity.

One is to analyze the data itself. For example if people tell you meat causes cancer, the best way is to find the actual scientific research on the topic and analyze it. And then look at other data sources (e.g. evolutionary past, physiological characteristics, and so on).

The other is to analyze the bearer of the data. Look at the person promoting this information and judge their competence in the field. If a random neighbor tells you meat causes cancer, that has less credibility than if a Nobel winning PhD Biology researcher tells you meat causes cancer. This method is less precise than the first, but much easier.

Experts can be wrong

The same mediocrity trap applies to everyone, even experts in a field. Someone who has a degree and 20 years of professional experience can get stuck in the arrogance curve as well. It’s even more likely when there is official authority involved.

So trust experts. But be mindful of the limits of anyone’s expertise.

Always learn

Duh, I know. But bears repeating. Nobody knows everything there is to know about any topic. So always try to learn.

Have fun

The best insight. When you don’t know everything there is to know, then you can have fun. You don’t have to be strict and do everything as prescribed because any variation is learning data.

🙏 Feel free to click the ❤ button on this post so more people can discover it on Substack. 😍 Tell me what you think in the comments.